A report was launched last week which, if people act upon even a fraction of the recommendations, might just trigger a quiet revolution which in the long run will benefit everyone.

The report was published by AkzoNobel, the global corporation behind Dulux, probably the world’s best-known paint brand. (For a longish but interesting read, the report is here). They know the complexities of paint (especially disposing of it) better than most, which is one of the reasons that they support Community Repaint – a network of organisations that collect and redistribute reusable and leftover paint to community groups and those in ‘social need’. FRP is one of the largest members of the network in terms of the volumes of paint we collect.

In the recycling world, what to do with leftover paint – other than throwing it away – is one of the trickiest unresolved problems. To begin with, there’s the sheer size of it – of the 400 million litres sold in the UK every year, 13% is thrown out. That’s 55 million litres – enough to fill more than twenty Olympic-sized swimming pools. And most of that (up to two-thirds) is perfectly usable.

At the moment, 99% of all waste paint is either burnt or buried – pretty toxic either way. Part of the difficulty is that unless we happen to be a professional painter/decorator, most of us will probably buy more paint than we need when we’re in DIY mode. Hence the stockpile. Most of us know that we can’t or shouldn’t just bin our leftover paint (much less pour it into the nearest drain), so it sits there until we need the space. Aggregate that across a few streets – never mind a whole borough – and you have the beginnings of your paint pool.

So what to do? The report sets out five areas of attention. Firstly, we all need to understand the size of the problem. Next, we need to demonstrate the potential for organisations like FRP to create colourful living spaces using recycled paint. This would mean more of projects like Colour The Capital, details of which can be found elsewhere on this site.

Thirdly, we need to look at whether re-use of recycled paint could form part of a more cost-effective option for local councils than disposal via incineration or landfill. And for this to work, council need to be actively engaged in the discussion. This happens more in some places than others. Alongside local government, Whitehall also needs to play their part through simplifying the regulatory process surrounding the disposal of paint, and through looking at how taxes are applied to its resale. Finally, we need a ‘big picture’ view of things to work out who else needs to be involved and engaged, across the paint industry and elsewhere.

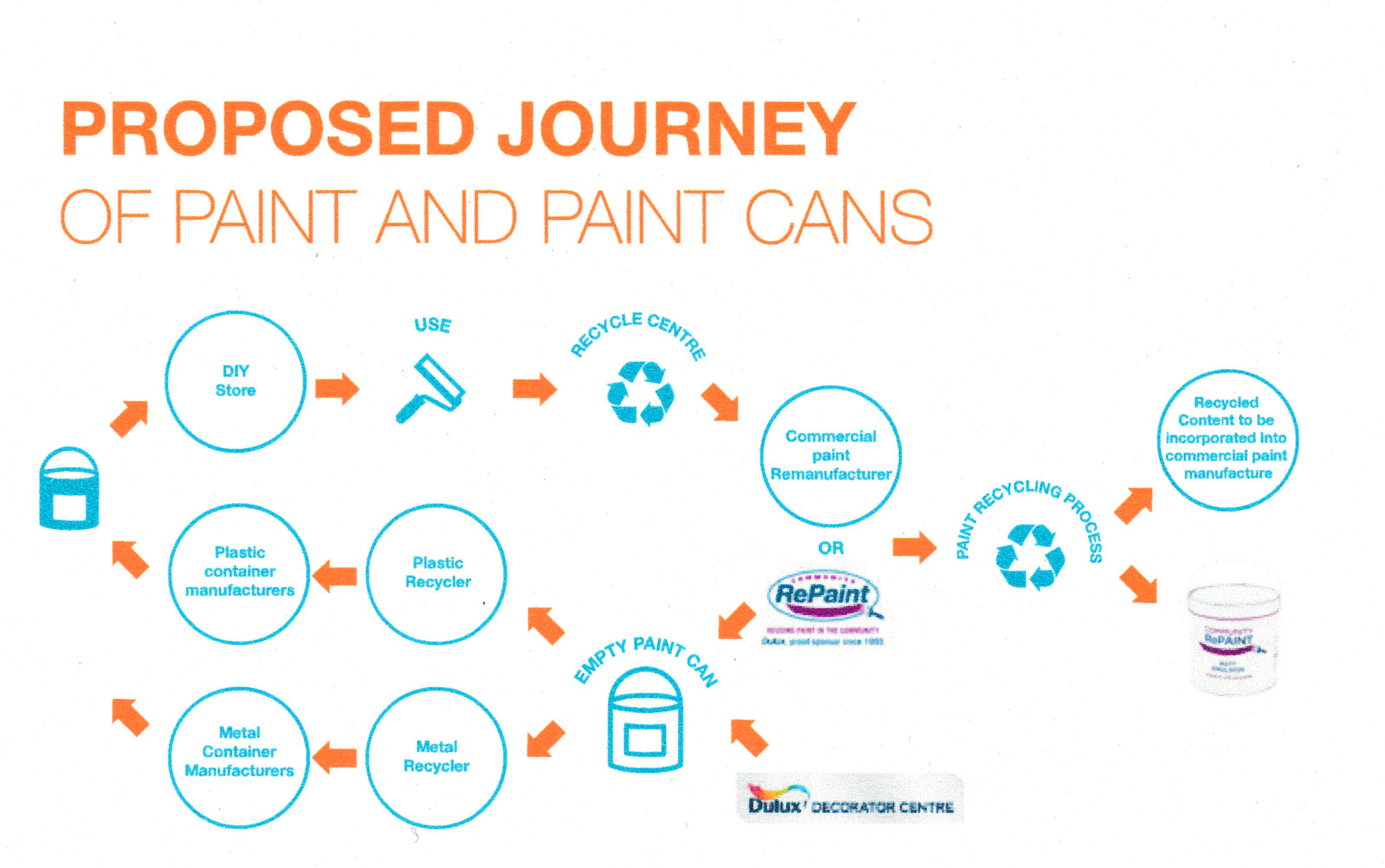

As with many social challenges, there are many pieces of the jigsaw to fit together, and our behaviour as individuals and consumers is part of the mix. At a simple level, it means buying less paint, or at least questioning whether you really need to buy brand new paint. If you’ve got paint already lying around (the average household has 17 tins of half-used paint stored somewhere), take a look at the diagram above this article (click on it to make it larger).

Not only does give you an idea as to where to take your surplus paint, it puts that action into a bigger picture and demonstrates how it feeds a virtuous cycle which not only does good, it also generates economic activity. The story behind the story of paint is about the growing ‘circular economy’ based on the reuse and recycling of a wide range of goods – a viable alternative given a growing realisation that ways of living based on a rinse-and-repeat cycle of ever-growing consumption followed by ever-growing waste no longer makes social, economic, or environmental sense.

So a big issue in scale, but also a solvable issue in terms of the thinking and behaviour required to address it. What it takes is us all raising our game a little, and it can be done. This is the art of the possible.